“Carbon” Capture Utilization & Storage (CCUS), Separating Fact from Fiction

Even if the world could effectively capture and permanently remove 1 billion tonnes of CO2 annually, the impact on temperature would be barely measurable. And the economic and ecological costs are enormous. Lars Schernikau lists the sobering facts.

CONTENT

2. How do we capture CO₂ & what are storage risks?

3. Utilizing CO₂, and make what?

4. Direct Air Capture, what logic?

5. The “climate impact” of CO₂ removal

6. Summary

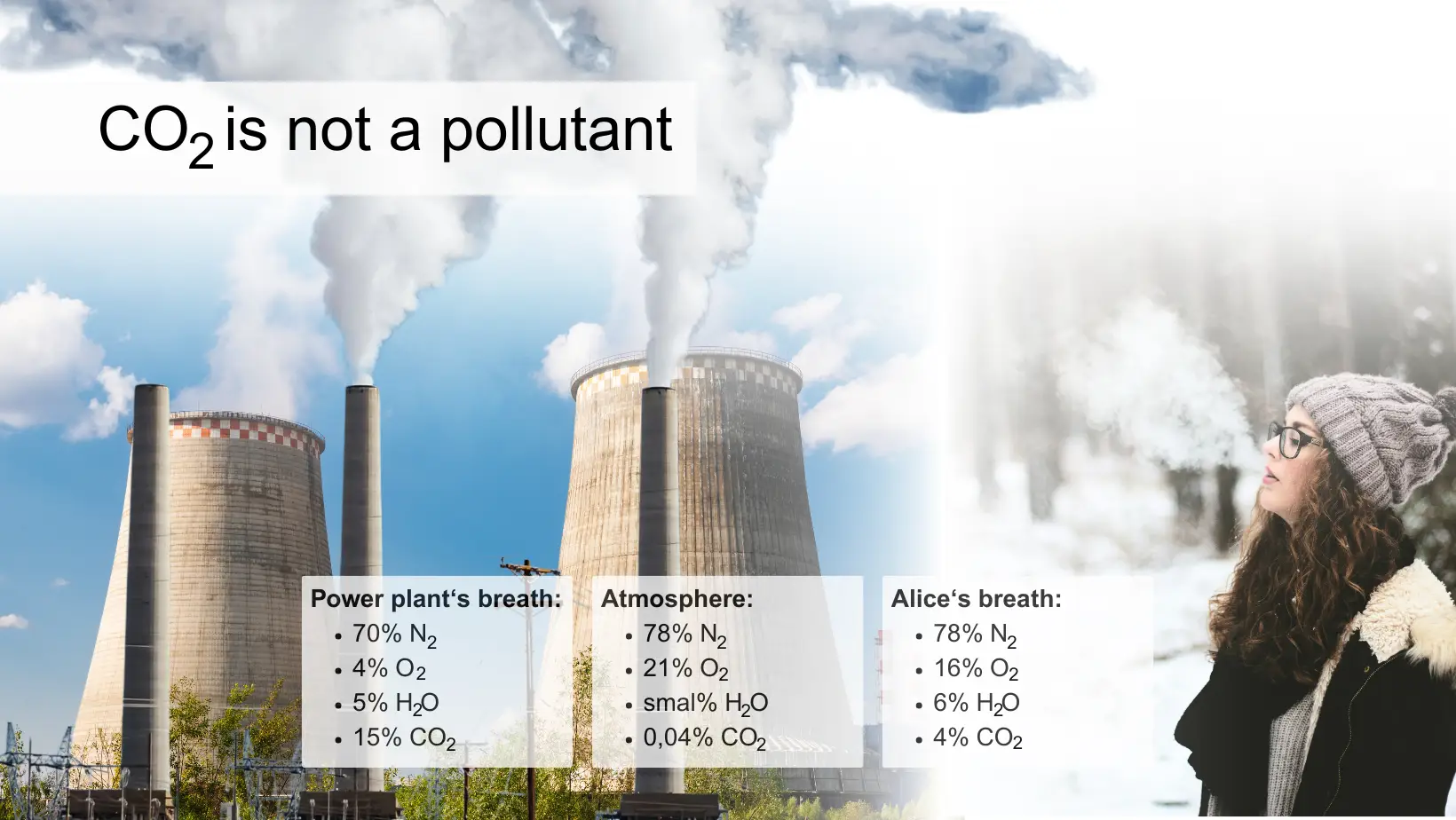

Fact 1: The carbon in your body originates from CO₂. CO₂ is a fundamental building block of all life on Earth, not a pollutant in itself. This is not a matter of belief, but of basic biochemistry.

CO₂, Life, and the Greenhouse Effect: CO₂ is a trace gas, currently around 420 parts per million in the atmosphere. It is also the primary source of carbon for all living organisms. The carbon in plants, animals, and human bodies originates almost entirely from atmospheric CO₂.

CO₂ is a greenhouse gas, but not a dominant one. Water vapour and clouds account for over 90% of the greenhouse effect. The warming impact of CO₂ decreases logarithmically, meaning each additional ton has a smaller effect than the previous one. A continuous increase in changes in CO₂ concentration therefore translate into smaller and smaller temperature changes. (WMO, [3]).

I am of the opinion that our current knowledge and computational methods fall well short of providing reliable predictive capability for the climate system. Whether elevated CO₂ levels are ultimately detrimental to or a benefit for life on Earth is a separate question. My blog does not address the causality between atmospheric CO₂ and these effects. For that discussion, I typically refer readers to Prof. Koonin’s book Unsettled and the writings of Prof Pielke’s writings.

Our society, largely driven by regulation, is seeking to remove CO₂ in order to measurably reduce atmospheric concentrations, with the aim of lowering temperatures or limiting future warming, and thereby hoping to reduce future extreme weather and sea-level rise.

Just for reference, there is ∼100,000 times more carbon per unit of volume in seawater than in air. Oceans are a natural sink of CO₂ as atmospheric concentrations rise for any reason. Over 50% of human emitted CO₂ is taken up by nature, probably close to 30% by oceans alone.

Fact 2: CO₂ is a trace gas that acts as a minor greenhouse gas, with diminishing impact on temperatures.

The idea of CO₂ removal exists because “Net-Zero” requires it. Emissions reduction alone do not meet stated targets, so large future volumes of CO₂ removal are assumed. For this reason, direct air capture (DAS) continues to attract investment despite limited practical value.

- The IPCC projects that between 6 and 10 billion tons of CO₂ (GtCO₂ ) would need to be removed annually by 2050 [1] to meet “Paris Agreement” goals

- IEA predicts in its net zero pathway that 6 billion tons of CO₂a. need to be removed by 2050 [4] FYI, IEA’s or anyone “net-zero” is actually not net-zero because CH4 will never reach net-zero and is not modelled to do so”.

- BCG estimates, in a second degree pathway, that 1 billion tons of CO₂ would need to be captured and permanently removed by 2035 [2]

- McKinsey estimates that $6-16 trillion investment in CO₂ removal would be required until 2050 ($0.5-2 trillion until 2030)

2. How do we capture CO₂ & what are storage risks?

It is stated that since 1996, in almost 30 years, less than 400 million tons of CO₂ have been captured and injected underground globally according to the first complete record of global underground CO₂ storage [5].

A substantial share of this CO₂ was used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) rather than permanent storage. Even among storage projects, not all injected CO₂ remains underground.

Realistically, cumulative net removal is likely closer to 100–200 million tons, achieved at a cost of tens of billions of dollars (total expenditure for this achievement is estimated somewhere between 60-120 billion USD). The obvious fact is that not all CO₂ was removed from the atmosphere, which caused the “climate impact” to be substantially lower than anticipated.

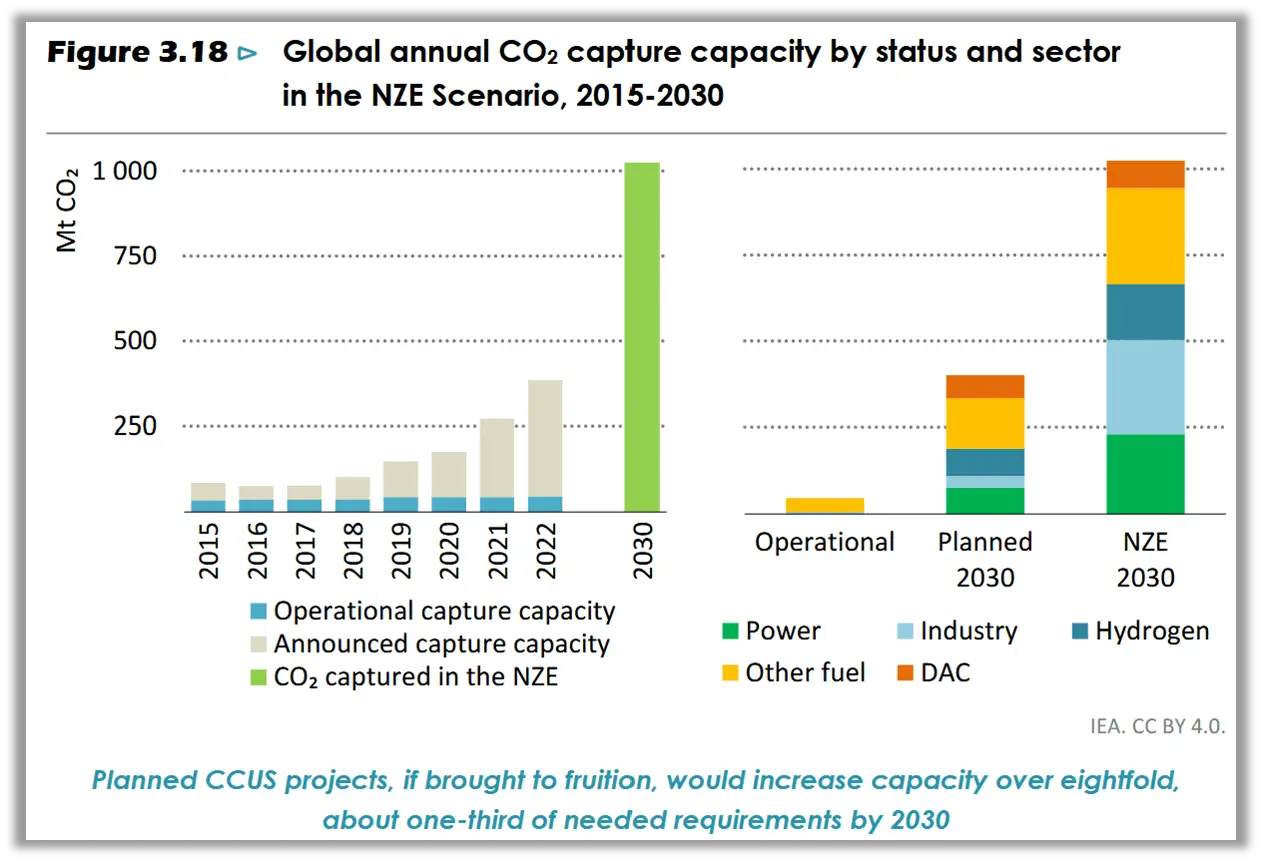

Global operational CCS capacity today (2025) is around 50 million tons per year, a negligible fraction of annual global emissions of ~70 billion tons of CO₂e in 2025 (inc. CH4 assuming GWP20).

Climate models and “net-zero” pathways assume billion-tonne-scale CO₂ removal within a decade as actual CCS deployment operates at million-tonne scale after 30 years of effort. This gap is not a matter of policy ambition but of physics, energy, and material constraints.

Capturing CO₂ is only the first step in any attempt at “permanent carbon dioxide removal.” In practice, CO₂ capture focuses on sources where CO₂ concentrations are already relatively high, mainly thermal power stations. Typical concentrations are:

- Coal-fired power plants (conventional combustion): ~12–15% CO₂ in the flue gas

- Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) plants (without CCS): ~6–8% CO₂ in the exhaust

- Coal is gasified, not combusted

- Pre-combustion CO₂ concentrations reach ~30–40%, which would be ideal for capture

- If CO₂ is not captured before combustion, this high concentration is lost through dilution

- Gas-fired power plants: ~3–5% CO₂ in the exhaust, despite higher overall fuel efficiency

- Direct Air Capture (DAC) for comparison: ~0.04% CO₂ in ambient air

Fact 3: For a modern coal-fired power plant with ~90% CCS, the all-in primary-energy requirement per delivered MWh is typically ~40% higher than without CCS (see Appendix 1)

This includes additional coal consumption, capture and compression, increased mining, handling and transport of the extra coal, and CO₂ transport and injection for storage, assuming all CO₂ is permanently removed, which in practice is not the case.

CCS does not make energy systems cleaner; it makes them larger, more complex, and less efficient.

Fact 4: The “energy cost of CCS” for a coal-fired power station is about 1 MWh per 1 ton of CO₂ (see Appendix 1) Considering the fuel multiplier for gas-fired power plants with CCS, we are looking at about 25% less, because gas-fired power stations tend to be more fuel efficient, despite the smaller CO₂ concentration in the exhaust stream.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Germany plans a CCS capacity of around 2 million tons of CO₂ per year. At this scale, the contribution is “climatically negligible”, illustrating the large gap between policy ambition and reality. [6]

When we look at the sub-optimal results of Australia’s flagship CCS project (see details on Gorgon in the Appendix below) and Germany’s climatically negligible ambitions, we see that CCS so far delivers neither reliability at scale nor meaningful impact when deployed.

Geological storage also carries risks. Another key challenge in carbon capture and storage (CCS) is the long‑term management of carbon dioxide after capture. The most widely proposed solution is geological storage, injecting CO₂ underground into depleted oil and gas reservoirs (where available near the capture site) or into deep saline aquifers. One of the most prominent examples of the latter is the CO₂ injection system developed as part of the Gorgon LNG Project in Western Australia, operated by a Chevron-led joint venture (with Shell and ExxonMobil as partners).

The Gorgon gas field off the coast of Western Australia was approved on condition the CCS project could and would capture 80 per cent of the CO₂ emitted, or 4 million tons a year. What it actually achieved in fiscal 2024 was just 1.6 million tons of CO₂ equivalent [7].

A further consideration for any subsurface CO₂ storage project is the consequence of unintended CO₂ release. Carbon dioxide is an asphyxiant and, being denser than air, may accumulate near ground level under certain conditions, especially in confined or low‑lying areas. At sufficiently high concentrations (5% and above, compared to 0.04% ambient CO₂ concentration) CO₂ can cause rapid loss of consciousness and death [8].

A natural release of CO₂ from a volcanic crater lake led to the asphyxiation deaths of roughly 1,700 people and thousands of animals in 1986. See Appendix 1 for more details.

In our own peer-reviewed research Schernikau/Smith 2022 “Climate Impacts’ of Fossil Fuels in Today’s Energy Systems” we come to the conclusion that, because of the CO2 and CH4 emissions of gas, natural gas is not “better for the climate” than coal. See Appendix 1 for more details and additional sources.

Figure 2: “Net-Zero” pathways assume large CO₂ removal

From IEA Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach – 2023 Update, p132 [4]

3. Utilizing CO₂, and make what?

CCU refers to CO₂ Capture and Utilisation. Please keep in mind that using CO₂ to produce fuels or chemicals does not remove it from the atmosphere. It means expending additional energy to make other products out of CO₂, usually fuels, that later release the same CO₂ or more.

As with all processes, capturing CO₂ and using the carbon it contains to produce new products makes sense only where it is both economically and energetically viable. Dr Bodo Wolf, a dear friend of mine, wrote a famous book in 2005 “Öl aus Sonne – Die Brennstoffformel der Erde” or “Oil from Sun, Earth’s fuel formular”. Wolf, a gasification expert, entrepreneur and inventor, described the logic of reusing the element carbon for fueling our world.

CO₂ is already in its lowest chemical energy state, as fully oxidised carbon. Any attempt to “use” CO₂ therefore requires the addition of energy, usually in large amounts.

- When “making” CO₂ into hydrocarbons or “e-fuels” (methanol, synthetic diesel/jet) one requires a lot of hydrogen, typically from electrolysis. Hydrogen dominates both the energy cost and monetary cost in these routes. See here for details on “green” hydrogen.

- For products such as urea or some carbonates, CO₂ is used as a feedstock and the “energy cost” can be lower

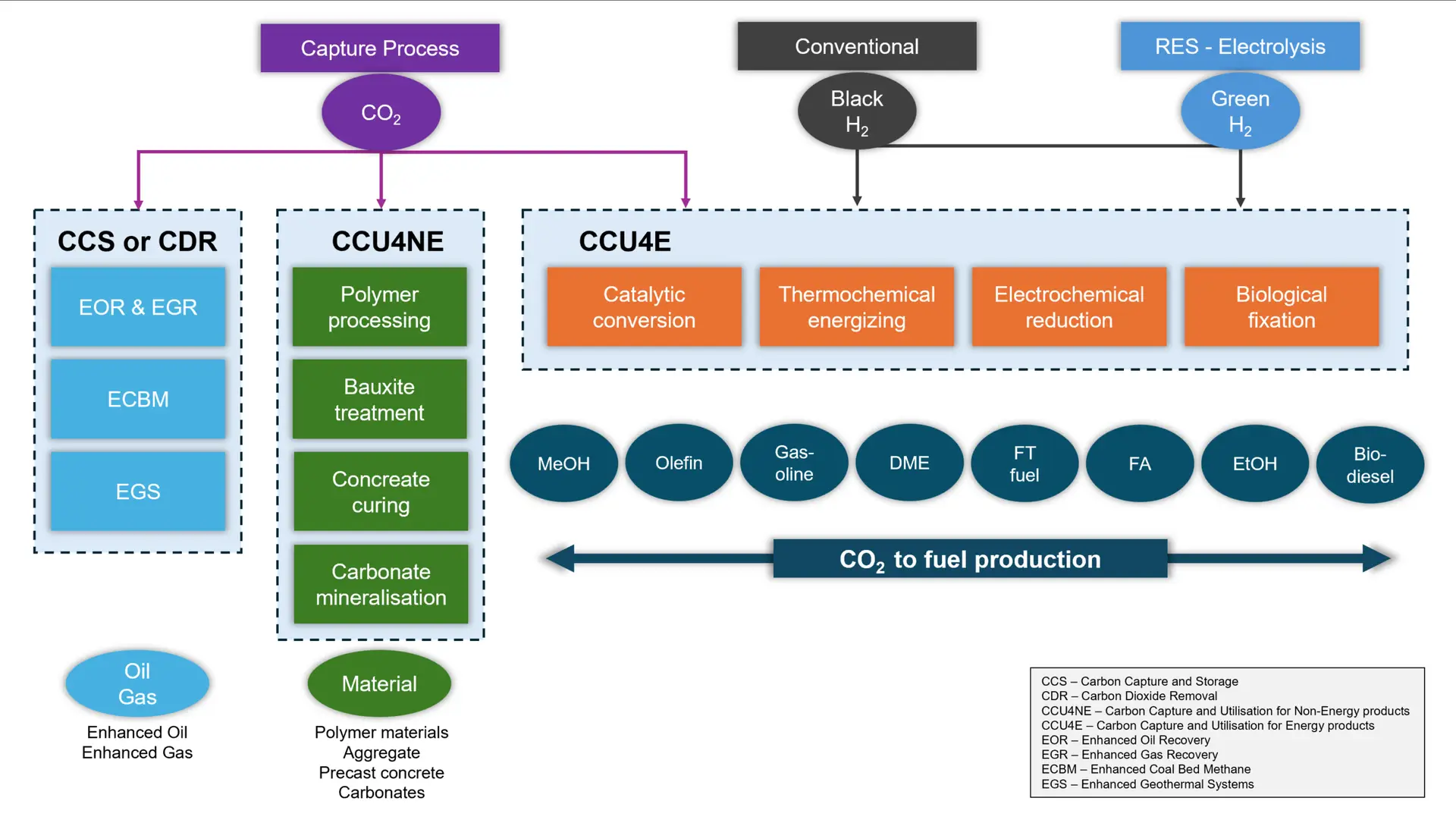

The industrial use of CO₂ can be classified into three main categories:

- CCS or CDR to sequester CO₂ underground or for enhanced oil recovery EOR

- carbon capture and utilization for non-energy products (CCU4NE),

- and for energy products (CCU4E), as show in below graph

Fact 5: CO₂ utilization to produce fuels represents an additional energy sink, and one that is more energy-intensive than CO₂ capture and storage CCS.

Figure 3: “Source Do et al 2022 [9]

Figure 4: Source: Carbon Industrial Usage – Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) [10]

Fact 6: Producing fuels from CO₂ using hydrogen carries a total system-level energy cost of 8–10+ MWh per tonne of CO₂, and the CO₂ is ultimately still released into the atmosphere. The “energy cost” for producing and refining oil is significantly lower.

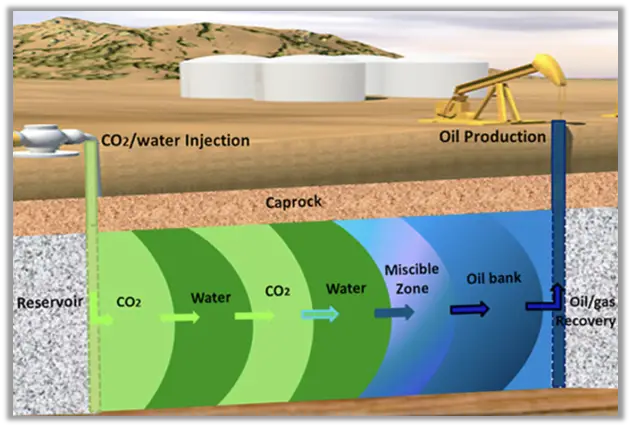

Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) is currently the most common use of captured CO₂. It is economically attractive and energy-positive because it produces oil, but its “climate benefit” is questionable.

EOR is a set of techniques used to extract oil that cannot be produced using normal primary or secondary methods. After a natural oil reservoir (pressure and waterflooding) is exhausted, EOR can substantially increase total oil recovery. EOR is usually economically attractive in mature oil fields

- Primary recovery gets ~10% of the oil

- Secondary recovery (water or gas injection) increases this to 20–40%

- EOR can increase recovery to 30–60%+

CO₂‑EOR is the most widely used method globally. CO₂ mixes with oil, making it flow more easily. It can store CO₂ underground while producing more oil. But the “climate benefit” is debated because EOR operations are energy‑intensive and the produced oil is later burned [11].

Fact 7: Enhanced Oil Recovery it the most common utilization of CO₂, with questionable “climate benefits” if any at all. However it makes economic sense and is energy positive because it produces oil that would otherwise not be recoverable.

4. Direct Air Capture, what logic?

Fact 8: DAC takes on physics, scale, and time simultaneously — and loses this fight against all three. The energy cost of DAC is ~2–4 MWh/ton CO₂.

Direct Air Capture (DAC) faces a fundamental problem: dilution. Atmospheric CO₂ makes up only about 0.04% of the air, meaning DAC systems must process enormous volumes of air to capture very small amounts of CO₂. If you thought carbon capture and storage was expensive, then direct air capture and storage will be far more expensive.

Separating a substance at such low concentrations is inherently energy-intensive. Most of the energy in DAC is spent moving air, not capturing CO₂. While capture from power-plant exhaust is already costly at much higher concentrations, doing so from ambient air multiplies the challenge by orders of magnitude.

If you assume the energy cost to be only ~2–4 MWh/ton CO₂, then 1 billion tons of CO₂ “removal” annually using DAC would be 2,000 to 4,000 TWh p.a. (8-15% of global electricity consumption).

DAC is therefore technically possible but practically unscalable. It exists mainly as a modelling assumption that allows “net-zero” scenarios to close mathematically, not as a realistic pathway for large-scale CO₂ removal.

Oh, there is one more “small point” to consider, the atmosphere and the surface waters are in dynamic equilibrium, which means that if we were to remove CO₂ from the atmosphere, then CO₂ would be released from the surface water back into the atmosphere. By the way, only about 45% of emitted CO₂ becomes – what is referred to as – “airborne”, the remainder is taken up by nature, our oceans and the biosphere. [12,13]

“As a general technology against climate change with a practical and significant impact at scale, DAC is completely infeasible.” (Prof Rasmussen, Cambridge, [13 ])

5. The “climate impact” of CO₂ removal

As discussed before, let’s assume that 200 million tons of CO₂ have actually been globally cumulatively removed using CCS since 1996… what was the “climate impact”?

The unpopular truth is…even if all CCS to date had permanently removed 200 million tons of CO₂, the climate impact would be effectively zero.

The IPCC offers a simplified MAGICC online calculator where you can enter the “avoided” CO₂ emissions in tons and see the impact on the temperatures in 75 years, in 2100. See Appendix 2 for more details on IPCC’s MAGICC.

Fact 9: Assuming that, during the past 30 year, CCUS removed about 200 million tons of CO₂ (that never resurfaced) from the atmosphere then, according to IPCCs MAGICC, 2100 temperatures reduced by ≈ 0.0001 °C Let’s round this up to zero as one cannot measure it, nor will it have any impact at all on extreme weather nor sea-levels

The estimated temperature impact of all historical CO₂ removal rounds to zero: it is not measurable and has no effect on extreme weather or sea-level rise.

As a rule of thumb using the IPCC’s MAGICC model, 1 billion tons of permanent CO₂ removal each year for 75 years and utilizing 8-15% of global electricity doing so would then result in only ≈0.035 °C less warming in 2100, still below detectability.

- Using the IPCC AR6 model framework, this corresponds to roughly 7 mm of avoided sea-level rise by 2100, also not measurable.

- For context, the IPCC projects that by 2100 global mean sea level would be about 10 cm lower at 1.5 °C warming than at 2 °C warming, with a wide uncertainty range of 4–16 cm; these projections remain disputed.

6. Summary

Let’s review the facts…

Appendix

Appendix 1: On CO2 capture in power plants

Links and Resources

[1] Carbon Removals: How to Scale a New Gigaton Industry | McKinsey. 2023. (link)

[2] BCG: Boosting Demand for Carbon Dioxide Removal. 2024. (link)

[3] WMO 2021, World Meterological Organization, Greenhouse gases, (link).

[4] IEA Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach – 2023 Update. 2023. (link)

[4a] IEA, Carbon Capture and Storage: What Can We Learn from the Project Track Record? 2024. (link) p6

[5] News, Norwegian SciTech. “First Complete Record of Global Underground CO₂ Storage.” Norwegian SciTech News, November 2025. (link)

[6] IEA: Germany 2025 – Analysis. 2025. (link) p.24

[7] RenewEconomy. “Gorgon AUS: Expensive Failure: Flagship Gorgon CCS Collects Less CO₂ in Worst Year.” December 2024. (link)

[8] Sources on danger of high concentration CO₂

- NIOSH — IDLH documentation for CO₂ (link)

- OSHA — exposure limits and technical method (link)

- Health and Safety Executive — CO₂ hazard guidance (link)

- Medical review: Permentier et al. (2017), hypercapnia effects (link)

[9] Do, Thai Ngan, Chanhee You, and Jiyong Kim. “Do et al 2022: A CO₂ Utilization Framework for Liquid Fuels and Chemical Production: Techno-Economic and Environmental Analysis.” Energy & Environmental Science 15, no. 1 (2022): 169–84. (link)

[10] Carbon Industrial Usage – Enhanced Oil Recovery EOR (link)

[11] Wikipeida on Enhanced Oil Recovery, EOR (link)

[12] “Why Scaling Direct Air Capture Is Practically Impossible | LinkedIn.” September 2025. (link)

[13] Prof Rasmussen, University of Cambridge, “Why Scaling Direct Air Capture Is Practically Impossible | LinkedIn.” September 2025. (link)

[14] BCG: Shifting the Direct Air Capture Paradigm.” BCG Global, June 2023. (link)

[15] According to US DOE NETL Cost and Performance Baseline for Fossil Energy Plants, Rev.5 (2023), adding 90% post-combustion CCS to an ultra-supercritical coal unit reduces net efficiency from 43.2% to 31.4% (LHV), implying roughly 35–40% higher fuel consumption per net MWh delivered (Table ES-1; Tables 3-14 and 3-22).”

This blog was previously published on The Unpopular Truth. You can subscribe to this blog here.

Lars Schernikau

Lars Schernikau, PhD has more than two decades of experience in the global energy and commodities industry. He began his career with the Boston Consulting Group in the U.S. and Germany, where from 1997 to 2003 he gained deep expertise in international coal, ore, and steel markets. He also managed a wind farm in Germany for three years, giving him first-hand experience in renewable energy operations.

As co-founder, shareholder, and former supervisory board member of HMS Bergbau AG and IchorCoal NV—international commodity marketing and mining companies—Lars has become a recognized authority on global energy economics. He is a frequent keynote speaker at energy and commodity forums worldwide and advises governments, banks, educational institutions, and corporations on macroeconomics, markets, and energy policy.

Lars is the author of several books, including The Unpopular Truth… About Electricity and the Future of Energy, which examines the economic realities of the transition from oil, coal, and gas to wind, solar, storage, and hydrogen. He has also written extensively on coking and thermal coal, contributing data-driven insights to the global energy conversation.

more news

Women are speaking out against the climate agenda

In the climate debate, it is mainly older, often retired male scientists who are challenging the prevailing paradigm. Female skeptics are few and far between. However, this has been changing recently. Both in science and the media, women are increasingly speaking out against what they see as a frightening and socially disruptive agenda. This is a positive development.

A review of The Frozen Climate Views of the IPCC, part 2

Clintel has analyzed IPCC’s Assessment Report 6 (AR6) and has published an important report on it, entitled: The Frozen Climate Views of the IPCC. It’s a report that provides many serious criticisms of the work carried out by the IPCC. Here you find the second and last part of a review of this important work by Clintel, recently published by the French website Climat et Vérité.

Javier Vinós on the Hunga Tonga Eruption and its extraordinary Climate Effects

In a recent ICSF/Clintel lecture, Dr. Javier Vinós argued that the January 15, 2022 Hunga Tonga eruption was the main cause of the extraordinary global climate anomalies of 2023–2024. He describes them as the first genuine multi-year global climate event in roughly 80 years, widely misinterpreted by mainstream analyses.