Dr Fritz Vahrenholt: Belém highlights the growing gap between climate targets and reality

In his newsletter, Dr Fritz Vahrenholt reports on the stalled climate diplomacy in Belém, the global increase in the use of fossil fuels and the risks of the planned tropical forest fund for taxpayers.

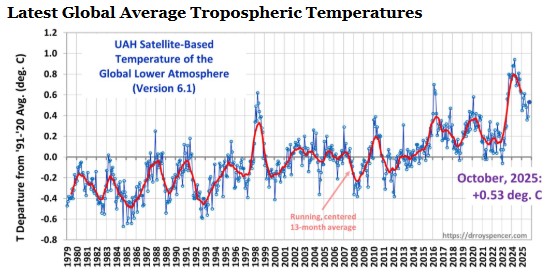

The global temperature in October remained unchanged compared to August. The cooling trend remains intact. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) expects a cool La Niña to develop in the Pacific this winter, which will lead to a further decline in global temperatures.

Belém – nothing but expenses

The 30th World Climate Conference in Belém is not yet over, but it is already clear that the event, billed as the “Conference of Truth,” will go down in history as a tipping point in the history of climate conferences. No heads of state from the four largest CO2-emitting nations—China (33%), the US (12%), India (8%), and Russia (5%)—are present in Belém. Even before the conference, the New York Times ran the headline: “The whole world has had enough of climate policy.” And the fact that Bill Gates, one of the biggest supporters and sponsors of climate policy, warned against excessive, short-sighted climate policy just 14 days before the conference and placed prosperity at the center of climate strategy came as a bombshell.

Glenn Beck, a prominent American television presenter, explains Bill Gates’ change of heart: “It’s not about science, it’s about Trump.” In other words, it’s not about conviction, it’s about damage control for his own company, which is planning billion-dollar investments in data centers in the US and around the world. And as things stand, these will have to rely on electricity from new gas-fired power plants in the short term, because reactivating old nuclear power plants will not be enough and building new ones will take several more years in the US.

For the climate conference in Belém, countries were required to report on their future plans for the use of coal, oil, and gas. The fact that only a third of them submitted a statement at all is an indication of the declining importance of climate issues in most countries around the world. But the reports that were submitted are telling. Most countries reported a continued increase in the use of coal, oil, and gas. By 2030, the reports show a 30% increase in global coal use, a 25% increase in oil use, and a 40% increase in gas use compared to 2015. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change hoped to reduce global CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2015, but now they continue to rise.

Only Europe remains steadfast in its goal of achieving net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050. Germany, the industrial heart of Europe, is even more ambitious and, according to Axel Bojanowski, is “the frontrunner among industrialized countries: it wants to be climate-neutral by 2045 – a self-destructive plan: Germany’s reduction will inevitably be offset by rising emissions in other EU countries. This is because European emissions trading ensures that emission rights that are not used in Germany are used up in other EU countries. It is becoming increasingly clear what the Wall Street Journal meant when it described Germany’s energy policy as the “silliest in the world.”

A few days before the conference, European countries agreed on a common goal of achieving a 90% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2040 compared to 1990 levels. Five percent of this voluntary commitment could come from emissions reductions abroad, which would of course also be expensive. The German Secretary of Environment celebrated this agreement as “good news for the German economy, as everyone now has the same competitive conditions.” This statement shows how little the German government and its secretaries understand about the global economy. It is as if German industry only exports goods to European countries. However, German goods enter a global market that is not burdened by CO2 taxes and high energy prices on German products and can therefore always offer them at lower prices. Fifty percent of exports go to countries outside the EU.

Chancellor Merz and his Environment Secretary Schneider are blatantly downplaying the situation in Germany. With its Climate Protection Act, Germany has imposed restrictions on itself that will have a highly painful impact in the coming years. Axel Bojanowski wrote: “The German Climate Protection Act, cemented by the Federal Constitutional Court, seems like a recipe for economic disaster. It allows Germany only a residual budget of 6.7 gigatons of CO2, which is likely to be used up by the early 2030s. According to the law, penalties, shutdowns, and restrictions on freedom will then be imposed in order to meet climate targets.”

6.7 gigatons was the remaining budget allowed after the Federal Constitutional Court’s ruling from 2020 onwards. To date, only 3.6 gigatons remain. Every year, the buffer is reduced by about 0.5 gigatons. By 2032 at the latest, the remaining budget will be used up and Germany will have reached the end of the line for the Federal Constitutional Court. This will happen in the next legislative period. Not in 2040.

And Chancellor Merz spreads reckless whitewashing in his five-minute speech in Belém in front of a half-empty hall: “The economy is not the problem. Our economy is the key to protecting our climate even better.” Doesn’t the chancellor know what a threatening situation our industry is in?

The Tropical Forest Fund scandal TFFF

The only outcome of the Belém conference will probably be the establishment of an investment fund proposed by Brazilian President Lula to finance the protection of tropical forests.

The fund works as follows: donor countries pay $25 billion into the fund. Private investors (investment funds) are expected to contribute $100 billion. Donor countries receive a return of around 4.0-4.8%, which corresponds to the return on their government bonds, as they usually have to raise the money through government debt. The return for private investors is 5.8 to 7.2%. The fund’s money is invested in government bonds from emerging markets, which yield comparatively high interest rates due to the higher risk involved (Brazilian government bonds are currently at 12.25%). Private investors are served first, followed by donor countries. If there is anything left after the distribution of profits to private investors and donor countries, the amount is distributed to 74 countries with tropical forests. It is hoped that this will generate 3-4 billion dollars annually for tropical forest countries.

The catch is that in order to attract investors in the first place, private investors are to be given priority in the order of payment: private investors first, then donor countries. In addition, donor countries must insure the fund against default. A default by an emerging market country can quickly lead to the fund’s insolvency. In that case, taxpayers in the donor countries would be held liable and, in extreme cases, lose their capital.

In preparation for Belém, there was fundamental disagreement between the Ministry of Finance and the Federal Chancellery regarding German participation in the fund. The Federal Chancellery was clearly in favor of participation and a contribution of at least $1 billion. It was assisted by the Department of Environment (secretary Schneider) and Department of Development Aid (secretary Alabali-Radovan). The Department of Finance under Lars Klingbeil strongly disagreed, seeing the fund as a billion-dollar risk and doubting the viability of the fund’s structure. And indeed, the model is structurally disadvantageous for German taxpayers. One could also say: we are subsidizing the returns of private investors with public money and assuming the default guarantee for Blackrock and Co. This is the reason why the Federal Department of Finance is stubbornly blocking Germany’s participation in the fund. It can be said without hesitation that the Federal Department of Finance has so far bravely defended the interests of German taxpayers against the interests of BlackRock and Co.

This is the reason why Chancellor Merz was unable to name a figure (“a substantial amount”) in Belém. The billion euros or dollars is now to be found in the budget review for the 2026 federal budget, which is taking place this week so that the federal budget can be passed on November 28. It is to be expected that the SPD will back down. But it could be a Pyrrhic victory for Chancellor Merz, who will then have visibly taken the interests of international financial investors into account. Especially if the fund were to run into difficulties.

Whether the fund will ultimately be established remains uncertain, as it will only come into effect once donor countries have committed to a total of $10 billion. So far, $5.6 billion has been raised (excluding Germany). The US and UK already have declined. If the fund is established, the first to benefit will be investment companies with high returns guaranteed by governments, followed by emerging markets, which will be able to sell their high-risk government bonds. Whether the tropical forest will benefit in this unmanageable financial jungle remains to be seen. The greatest risk remains with the donor countries, which are putting their taxpayers’ money at risk with the catchy story of saving the rainforest.

Dr. Fritz Vahrenholt

The above articles are taken from Dr Fritz Vahrenholt‘s newsletter dated 12 November 2025. You can subscribe to this newsletter here.

more news

Ed Miliband is the last fool standing on Net Zero

As the United States moves to reconsider key climate regulations, Britain’s aggressive push toward Net Zero is drawing increasing scrutiny. In this commentary, Matt Ridley argues that unilateral decarbonisation risks leaving the UK economically isolated while much of the world shifts course.

Climate change computer projections are manifestly false and dangerously misleading

The alleged threat to the planet from human caused climate change has been at the forefront of Australian politics over the recent half century. Every year, just before meetings of the UN Conference of the Parties (COP) to the Climate Change Convention, slight increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide and global temperature are portrayed in the media as harbingers of future doom. Every extreme weather event is made out to be an ill omen of what is to come unless fossil fuels are eliminated.

Glacier fluctuations don’t yet support recent anthropogenic warming

Holocene glacier records show that glaciers worldwide reached their greatest extent during the Little Ice Age and were generally smaller during earlier warm periods. While glacier length is a valuable long-term regional climate indicator, the evidence does not clearly support the idea of uniform, synchronous global warming.