[There is also a Greek version of the post—Υπάρχει και ελληνική έκδοση της ανάρτησης]

By now, I have published 41 peer-reviewed papers about climate—out of my total of 258 papers in journals and my total of 1000 works recognized by Google Scholar.1

The peer review system has had bad facets ever since I started writing papers (around 1990). I had been involved in it in several roles, author, reviewer, editor, and tried to make suggestions for improvement, by writing editorials and papers about it.

But instead of being improved, the system worsened a lot, especially for papers proposing new ideas on sensitive issues, such as climate and health. Publishers, editors and reviewers have largely abdicated their role and become the guardians of a decayed and corrupt political system related to global governance. When it comes to climate, they behave as climinions or climorns, usually with a hidden smugness that by rejecting a “heretical” paper they are saving the planet as activists.

If the effort to publish a conventional paper of medium (or even low) quality is A, that to publish a high-quality paper that contradicts conventional wisdom is about 4A. Why? Because often the write-up to rebut the negative comments becomes equivalent to writing another paper. And because if the paper is good, it usually gets rejected several times and has to be resubmitted to other journals until it is published.

From the above, I suppose it is understandable how much I have been beaten up for publishing my 41 climate papers. As I’m in favour of full transparency in the peer-review process, I have posted online all materials for the rejections I’ve received. Most of the rejected ones are my very best. A characteristic example is my latest paper:

D. Koutsoyiannis, Relative importance of carbon dioxide and water in the greenhouse effect: Does the tail wag the dog?, Science of Climate Change, 4 (2), 36–78, doi:10.53234/scc202411/01, 2024.

In this, I have included as Supplementary Information the earlier rejections of three journals (a 73-page document—click on “Prehistory of rejections” on the above link to my web site or on “You find supplementary data here” on the official journal’s site).

Another interesting example is my recent paper:

D. Koutsoyiannis, Stochastic assessment of temperature – CO₂ causal relationship in climate from the Phanerozoic through modern times, Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, 21 (7), 6560–6602, doi:10.3934/mbe.2024287, 2024.

This one was not rejected, but the effort to rebut the demolitionist review comments was just as great. I have posted my replies in a separate document here:

I feel exhausted from those adventures. On the other hand, I am pleased as I feel that I have won.

First, I have managed to publish almost all my climate-related papers—41 out of 42 (one received multiple rejections in 2012-2015, after which I quit and posted it on ResearchGate). Especially, in the last five years I published all my 16 climate related papers, listed in the link I gave above.

Second, the papers resisted climalarmists’ attacks to the journals putting pressure to retract my papers. I refer to them in my hen’s and serpent’s egg essay I mentioned above. The single post-publication change, which actually is very mild, was for my paper published in an EGU journal:

D. Koutsoyiannis, Revisiting the global hydrological cycle: is it intensifying?, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 24, 3899–3932, doi:10.5194/hess-24-3899-2020, 2020.

Specifically, after its publication and because of climalarmists’s complaints, the editors asked me, and I accepted, to replace the links to two of my presentations, which I had included in the Acknowledgments section of the paper, with a link to my personal web site. These two presentations whose links were removed are:

D. Koutsoyiannis, Personal knowable moments (DK-moments) for high-order characterization of coincidence in totalitarianism, Self-organized lecture, doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.23117.38885/1, Bologna, Italy, 17 December 2019.

D. Koutsoyiannis, The political origin of the climate change agenda, Self-organized lecture, doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.10223.05283, School of Civil Engineering – National Technical University of Athens, Athens, 14 April 2020.

Third, two formal Commentaries on two of the papers, which were submitted and published in two journals, despite the efforts of the Commentators, failed to find any errors in my papers and increased my confidence on the results and conclusions of the papers. I guess there were more Commentaries submitted, but they must have been rejected.

Fourth, the papers were widely disseminated and discussed. For example, the EGU paper I mentioned, which already has 160 Google Scholar citations, was the most-read of the journal for 2020:

Screenshot from EGU’s 2020 web site

Another paper, published in the Royal Society’s Proceedings, is listed, among the most downloaded articles, as the second ever among all categories, or the first ever in the category of research articles:

Screenshot from Royal’ Society’s web site

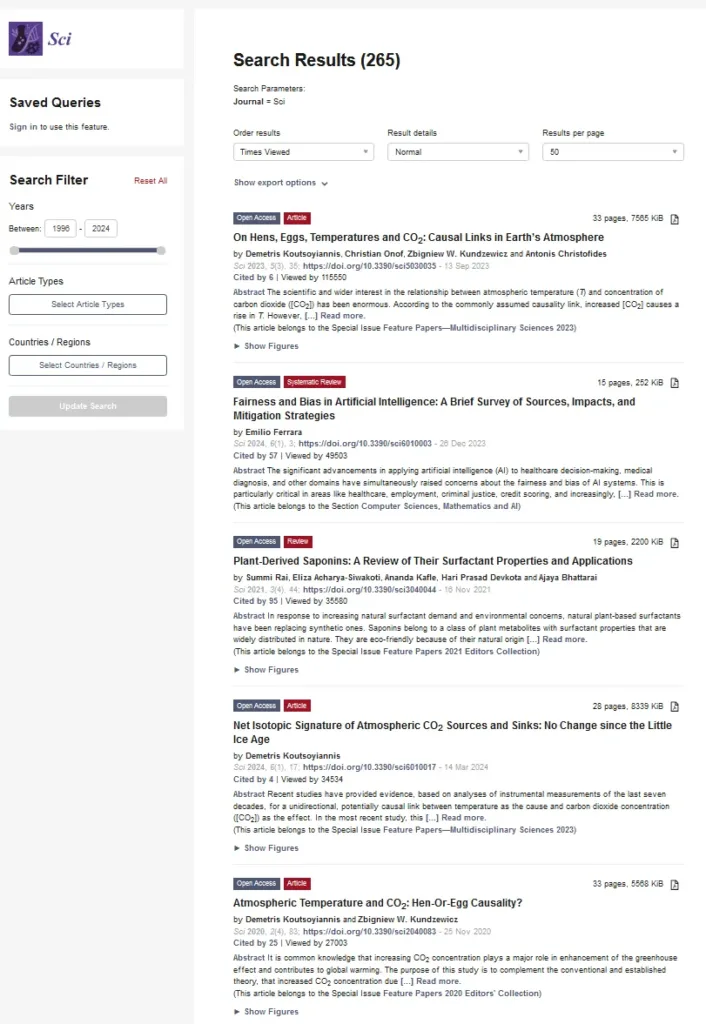

Three other papers are among the top five (in terms of views) articles in MDPI’s journal Sci, one of which is the first ever (by far):

Screenshot from the web site of the journal Sci

That first in the above list of five in Sci, thanks to the generosity of Judith Curry, was discussed intensively at her blog. I compiled the whole discussion, featuring about 1000 contributions (among which 177 are my own replies to comments) in 184 groups from 83 commenters, into a book-sized (372 pages) document.

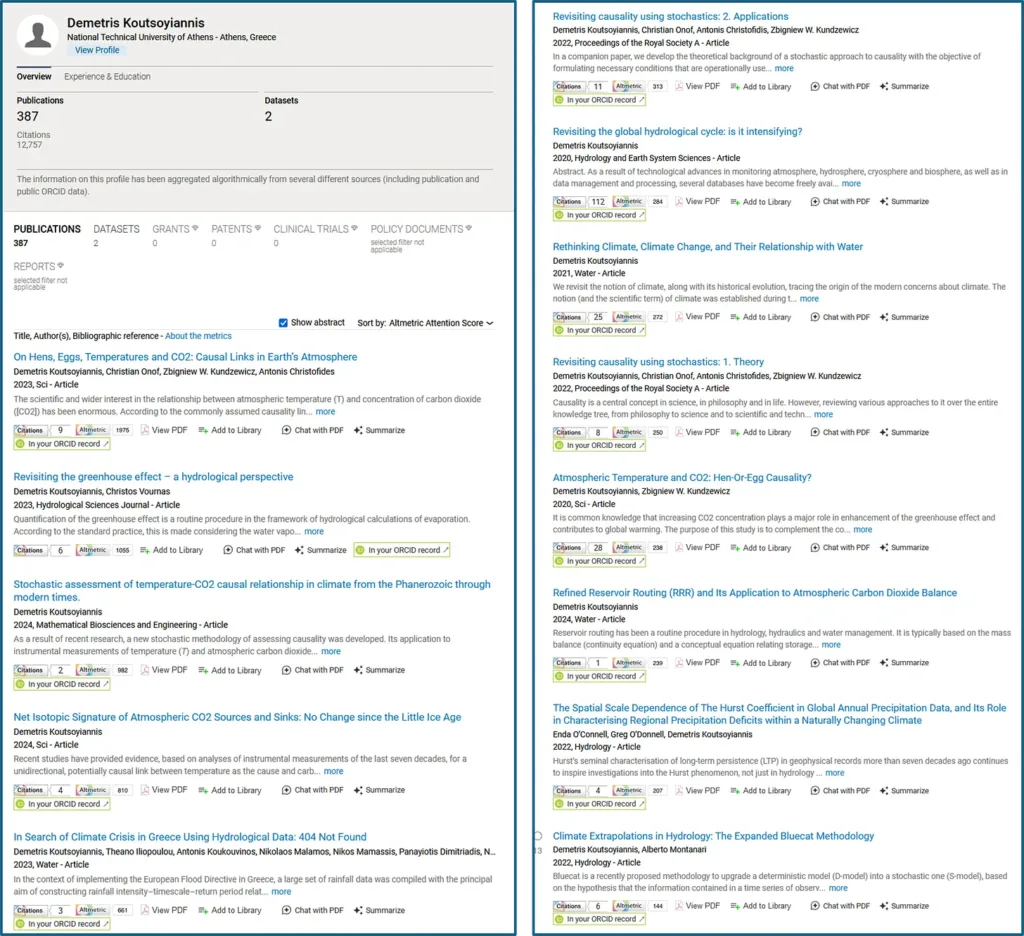

The other recent articles were also discussed in blogs and social media, and for this reason they have high altmetric scores:

Screenshots from the Dimensions platform with the Altmetric scores of my recent climate-related papers.

Fifth—and that is the reason for having given so many details in the fourth as evidence for the fifth—the extensive discussion has been very useful to me. The discussers may have been critical and may have persisted in their criticisms, but in my view no error was spotted in any of the papers. On the contrary, I had confirmations of my results by two independent colleagues, whom I did not know before.2 All papers held up well. And the criticisms prompted me to produce more papers to rebut them.

I feel that I have now formed a comprehensive view of climate, which I will present in future posts. But of course there may be errors in my work, despite the failure of volunteers to spot them. And of course, discovering and correcting errors is the way science progresses.

This article was originally published on Climath, the personal blog of Demetris Koutsoyiannis.