By Judith Curry

Original post on Climate Etc.

The Inflation Reduction Act that has passed in the US Senate contains a healthy dose of funding for energy and climate initiatives. There is much discussion as to why this bill looks like it will pass, when previous climate bills (carbon tax, carbon cap and trade) failed.

The Senate bill includes billions of dollars in tax credits and subsidies for clean energy and electric vehicles. In addition to renewable-energy funding, there is also commitment to federal oil and gas expansion, albeit with fines for excessive methane leakage. The bill includes climate resiliency funding for tribal governments and Native Hawaiians and other disadvantaged areas disproportionately impacted by pollution and climate warming. Funds are also allocated to tackle drought remediation in the West.

I’ve received requests to write on this topic, here are some bits and pieces that I’ve pulled together. My main points:

- Post-apocalyptic climate politics have a much better chance of succeeding than fear-driven apocalyptic climate politics

- Energy policy should be detached from climate policy to make a robust transition to a 21st century energy system that emphasizes abundant, cheap, reliable and secure power with minimal impact on the environment (including land use).

Apocalyptic climate politics

Motivated by international treaties and the UNFCCC Paris Agreement, countries and municipalities are declaring a “climate emergency” or “crisis” that requires urgent and strong climate policies to avoid both local and global catastrophe.

Business-as-usual climate policy is based on what has been referred to as the politics of “climate scarcity” (Asayama), whereby there is an upper limit to the level of warming (and thereby CO2 emissions) that must not be exceeded to avoid dangerous climate change. The politics of climate scarcity is associated with the politics of energy and material scarcity, blaming climate change on extravagant lifestyles and requiring a long period of belt-tightening if we are to survive the crisis.

The failure of the world’s governments to make much headway in reducing emissions is blamed on several factors. The main impediment to progress is blamed on fossil fuel companies, who wield power through political influence via financial contributions and propaganda. Capitalism is being blamed because manufacturers, farmers and others need fossil fuels to produce food and equipment needed by the economy and general population. Democracy is being blamed, since democratic decision making is too slow and sometimes people don’t make the “right” decision. Arguments are being made for degrowth, which is the idea that economic growth is environmentally unsustainable and should be halted, at least in wealthy countries.

With the failure of most countries to significantly reduce CO2 emissions, activists and governments are using “random gambits to kneecap fossil fuel production.” These include restricting permits to for fossil fuel production, cancelling oil and gas pipelines, getting organizations to divest their funds from fossil fuel companies, and restricting access to loans and other financial resources for fossil fuel companies.

Attempts to limit CO2 emissions from the demand side by imposing carbon taxes have been politically very unpopular. Even among people who are supportive of addressing the climate change problem, they are unwilling to pay higher energy prices. The politics of scarcity is not an easy sell, particularly when framed in terms of anti-democracy, anti-capitalism and degrowth. The politics of alarm and fear and scarcity haven’t worked. However, letting go of the apocalyptic rhetoric is difficult for those who have built careers based on climate catastrophism.

Climate politics business-as-usual (the apocalyptic version) expects people in developed countries to exercise energy and material restraint for the altruistic motives of “saving the climate”, while at the same time slowing down development in Africa by not supporting access to their own energy resources. While the vast majority of people believe that climate change is a real problem, they fear a future without cheap and abundant fuel and continued economic expansion much more than they fear climate change. Making people’s energy less abundant and/or increasing its price is politically toxic unless there is an urgent, short-term need for austerity.

Framework for a post-apocalyptic politics

Lets face it — the climate “crisis” isn’t what it used to be. Circa 2013 with publication of the IPCC AR5, RCP8.5 was regarded as the business-as-usual emissions scenario, with expected warming of 4 to 5oC. Now there is growing acceptance that RCP8.5 is implausible, and RCP4.5 is arguably the current business-as-usual emissions scenario. Only a few years ago, an emissions trajectory that followed RCP4.5 with 2 to 3oC warming was regarded as climate policy success. Now that limiting warming to 2oC seems to be in reach (now deemed to be the “threshold of catastrophe”), the goal posts were moved in 2018 to reduce the target to 1.5oC. A few weeks ago, in defending its decision to issue fossil fuel prospecting permits in spite of declaring a climate emergency, the New Zealand government stated that the climate crisis was “insufficient” to halt oil and gas exploration. Climate change is indeed an “insufficient” crisis.

Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations (1776) points the way towards a post-apocalyptic climate politics.

“We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages”.

There is growing support for a climate politics that harnesses enlightened self-interest, rather than focusing on austerity. In other words: carrots, not sticks.

There are three major political issues that fall under the climate umbrella:

- The desire for clean, abundant and cheap energy for the global population

- The desire to reduce vulnerability to extreme weather and climate events

- Concerns about rising atmospheric concentrations on CO2 and its impact on the climate

Issues #1 and #2 are primarily dealt with by national and subnational entities, and receive widespread political and economic support if they support local self-interests. Issue #3 is politically controversial since international policies have attempted a top-down approach that controls #1 and #2 by the emphasis on rapid reduction of fossil fuel emissions, with the specter of energy scarcity and a redirection of international funds away from development and adaptation.

Focusing on issues #1 and #2 is a quieter kind of climate politics (“don’t mention the climate”, an adaptation of a Fawlty Towers skit “don’t mention the war”), which doesn’t require the apocalyptic rhetoric but rather addresses concerns and opportunities that people are enthusiastic about addressing. Actions taken willingly and enthusiastically are more effective politically and have higher moral legitimacy because of the absence of coercion. A focus on issues #1 and #2 supports the flourishing and thriving of the global population, which should act to de-escalate the political controversies associated with the climate change issue.

Further splitting off issues like water resources and food security from the climate issue allows for addressing real problems at a more local level, without expecting a reduction in atmospheric CO2 concentrations to actually ameliorate anything on decadal time scales.

Once we acknowledge that we don’t currently know how to fully address the challenge of stabilizing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at a low level on the timescale of decades, we can search for new and more effective approaches for issues #1 and #2 and other ancillary issues that currently live under the climate umbrella, all the while focusing on supporting human flourishing and thriving in the 21st century.

If we deal with all of these other issues, human-caused climate change becomes something we don’t even need to talk about – we will be prospering because of abundant and inexpensive energy and can afford to reduce our vulnerability to climate change (both natural and human-caused).

And incidentally, CO2 emissions will be reduced. Matt Taibbi’s “green vortex” shows how the learning curve for new green technologies will continue to accelerate.

US Senate IRA bill

Why did the Senate IRA bill succeed where other US attempts at climate legislation failed?

One narrative is that the adverse impacts from recent extreme weather events has finally overwhelmed the “evil” strategy of oil, gas and coal companies of sowing doubt about the severity of climate change.

The other, more convincing narrative is that this bill offered monetary incentives to industries and consumers to switch to clean energy, with no mention of energy- or CO2– related taxes. Essentially, lawmakers replaced the sticks with carrots. Time for the environmental economists to eat humble pie.

A further reason for the success was labelling this as Inflation Reduction Act. This (mostly) misnomer is politically very useful in avoiding the reflexive association of this bill with often nutty climate policies driven by the apocalyptic version of climate politics.

The bill also includes provisions for gas and oil exploration. While the apocalyptites regard this as a deep flaw, it is actually an important feature. Any efforts to reduce to reduce CO2 emissions needs to acknowledge that fossil fuels are needed to fuel the 21st century energy transition.

Attempts to speed up the transition away from fossil fuels by restricting the production of fossil fuels and new generating plants has backfired by making many countries reliant on Russia’s fossil fuels. The geopolitical instability associated with Russia’s war against Ukraine highlights the importance of having multiple options and safety margins – key characteristics of robustness. Safety margin strategies in electric power systems include redundancy, a range of different power sources, and reserve power. Overcapacity should be a feature of future energy systems, not a bug. And for now, this needs to include fossil fuels.

So while this bill was a political win, I have to say if I was in charge of $400B to support the energy transition I would have focused on R&D for advanced nuclear and geothermal plus smart microgrids.

21st century energy transition

Everyone wants cheap, abundant, reliable, secure and clean energy.

While fossil fuels have fueled human progress in the 20th and early 21st centuries, there is a strong rationale for reducing our reliance on fossil fuels for energy – independent of their impact on atmospheric CO2 concentrations and air and water quality. Mining for fossil fuels has large, continuing economic and environmental costs. Fossil fuels will become increasingly expensive to extract by the 22nd century. The Russian war on Ukraine highlights the vulnerability of fossil fuel supply chains and price spikes to geopolitical instability.

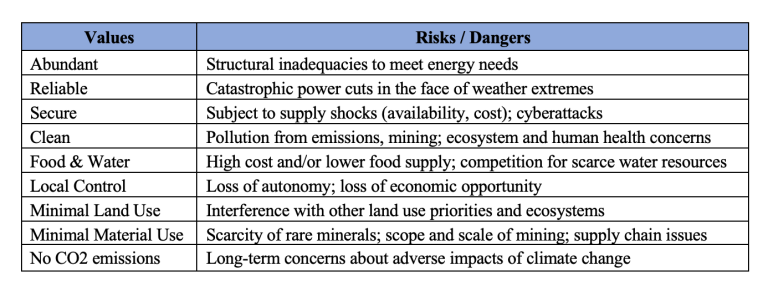

There are many reasons to support a new energy system (independent of CO2 emissions) that will set the stage for global human progress in the 21st century. Here are some considerations for the 21st century energy systems, outlined in terms of values and risks/dangers

The 21st century energy transition can be facilitated with minimal regrets by:

- Accepting that the world will continue to need and desire much more energy – energy austerity such as during the 1970s is off the table.

- Accepting that we will need more fossil fuels in the near term to maintain energy security and reliability and to facilitate the transition in terms of developing and implementing new, cleaner technologies.

- Continuing to develop and test a range of options for energy production, transmission and other technologies that address goals of lessening the environmental impact of energy production, CO2 emissions and other societal values

- Using the next two to three decades as a learning period with new technologies, experimentation and intelligent trial and error (let the “green vortex” work), without the restrictions of near-term targets for CO2

In the near term, laying the foundation for zero-carbon electricity is substantially more important than trying to immediately stamp out fossil fuel use. Africa should be allowed to develop its own natural gas resources. The transition should focus on developing and deploying new sources of clean energy. The transition should not focus on eliminating electricity from fossil fuels, since we will need much more energy to support the materials required for renewable energy and battery storage and building nuclear power plants, as well as to support growing numbers of electric vehicles and heat pumps.

The build out of wind, solar and natural gas can fuel the transition, but this combination probably will not survive competition from new and better technologies that become available in the coming decades. The push for weather-based renewable energy – wind, solar, hydro – seems somewhat ironic to me. One of the main motivations for transitioning away from fossil fuels is to avoid the extreme weather that is alleged to be associated with increasing CO2 levels. So why subject our energy supply to the vagaries of water droughts, wind droughts, icing and forest fires? In any event, the growth of renewable energy has been a substantial boon to private sector weather forecasting companies that support the electric utilities sector.

Transmission upgrades needs to play a key role in the transition. Modernization of the transition grid is needed to enhance reliability and resiliency, improve cybersecurity and prevent outages due to extreme weather. Smart grids can allow advanced control of load supply and demand. Developing and evaluating microgrids would substantially support the learning curve for incorporating distributed energy resources to improve transmission and make it more flexible.

Transformation of the electric power sector will require considerable inputs of raw materials, including rare earth and semi-/precious metals and structural materials such as cement steel, and fiberglass. Apart from the amount of energy required to mine, process and refine these materials, some critical materials are concentrated in a few countries, which will change the geopolitical dynamics. Building stable supply chains for critical materials is critical for the growth of wind, solar and battery storage. A circular economy with reuse and recycling will help minimize environmental impacts and supply chain shocks. Technologies that use low cost, readily available materials will have an advantage in being adopted.

How fast can the transition occur? China has developed its energy systems at an astonishing speed. An autocratic government with a top-down energy strategy can rapidly implement changes. However, there are disadvantages to such an autocratic approach relative to the more chaotic, bottom-up approach of developing energy systems in the U.S. Yes, making changes to an electric utility system in the U.S. must confront permitting, regulations, public approval, litigation, delays, cost overruns and an archaic financial model for electric utilities. However, the more bottom-up approach (individual states and electric utility companies) provides many different opportunities to experiment and learn, thus producing in the end an evolution of electric power systems that may be more anti-fragile with a broader array of options.

Bottom line: Focus on the energy transition, not near-term CO2 emissions. Clean is one of the major values, and the CO2 emissions will eventually reduce. Overall a more rapid transition will be facilitated if we don’t unduly focus on CO2 emissions and meeting near term emissions targets.