By Andy May

SAR is an abbreviation for the second IPCC assessment report, Climate Change 1995 (IPCC, 1996). As explained in my new book, Politics and Climate Change: A History, this IPCC report was a turning point in the debate over catastrophic human-caused climate change. The first IPCC report, “FAR,” was written under the chairmanship of Bert Bolin. At the time FAR was completed and published, circa 1990, Margaret Thatcher, the “Iron Lady,” was Prime Minister of the U.K. and a fervent climate change alarmist. Bert Bolin thought she was “seriously misinformed.” The conclusion of FAR was:

“global-mean surface air temperature has increased by 0.3°C to 0.6°C over the last 100 years … The size of this warming is broadly consistent with predictions of climate models, but it is also of the same magnitude as natural climate variability. … The unequivocal detection of the enhanced greenhouse effect from observations is not likely for a decade or more.” (IPCC, 1992, p. 6)

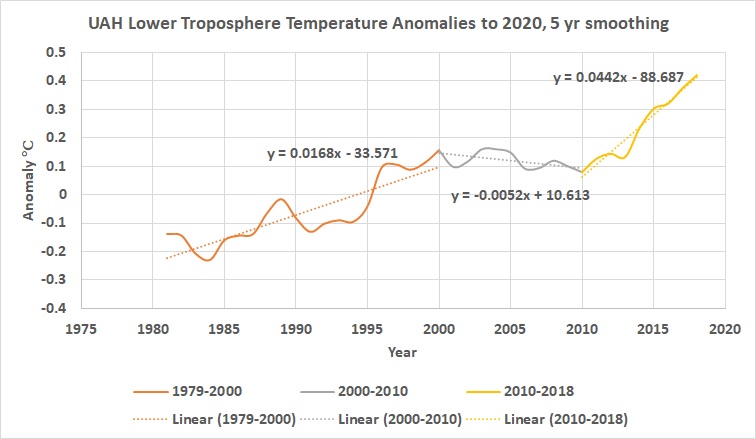

As we saw in the earlier post on Roger Revelle, he said the same thing in 1988 to Senator Tim Wirth. Revelle, Fred Singer and Chauncey Starr also said a decade was needed to determine if humans were involved in warming (Singer, Revelle, & Starr, 1991). A decade later, in 2002, temperatures were falling from their peak during the 1998 El Niño. They continued to fall until 2010, as seen in Figure 1. In Figure 1, we smoothed the UAH tropospheric temperature anomalies with a five-year moving average to reduce the ENSO (La Niña and El Niño) anomalies and emphasize the longer-term climatic trends. The full range of data is from December 1978 to September 2020, but due to the smoothing we can only plot 1981 to 2018.

In Figure 2 we see that the five-year smoothed tropospheric temperatures rise 0.17 degrees per decade from 1979 to 2000, then they decline at 0.05 degrees per decade from 2000 to 2010, and then rise again from 2010 to 2018 at 0.4 degrees per decade.

While temperatures have risen and fallen over the past 40 years, CO2 increased steadily the whole time. We can easily see that Bert Bolin, Fred Singer, Chauncey Starr, and Roger Revelle were correct to be cautious about attributing most of global warming to CO2. If CO2 is warming the planet, Figure 1 shows there are other forces that are powerful enough to reverse the warming for up to ten years. Is the underlying, longer-term, warming trend of 0.14°C/decade, mostly natural or mostly human? With a rate that small does it matter?

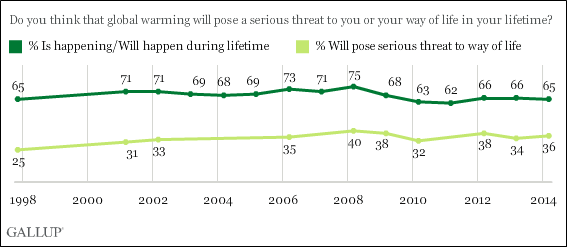

The cream of the scientific community saw no need for urgent action or for alarm in the early 1990s. Many politicians disagreed, they wanted action now. The public, from 1998 to 2019 has remained unconvinced that global warming or climate change is dangerous in their lifetime. Since 1997, polls have shown that between 60% and 75% of the U.S. public do not believe that global warming poses a threat within their lifetime (Nisbet & Myers, 2007). The Washington Post breathlessly proclaims that “Americans increasingly see climate change as a crisis,” in 2019, and then presents a poll that says 62% of the public don’t believe it. This is approximately what the public has said since 1997 (Dennis, Mufson, & Clement, 2019). Figure 1 below shows how steady public opinion has been:

Nobody watches the polls like a politician, and they desperately wanted to change them. As H. L. Mencken wrote in 1918, “The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with a series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary.” (Mencken, 1918). Another way of putting it, if you frighten a free and democratic public enough, they will give up their individual rights and even their country for safety and security. Lucky for us it hasn’t worked yet.

The scientists who wrote FAR, said they could not see any direct evidence of a human contribution to global warming or climate change. This did not help the political cause, which was to use climate change as an excuse to redistribute the wealth of the western countries to the rest of the world. They nearly achieved this goal with the Kyoto treaty, signed by Al Gore in 1997, but that is another story. Let us just say we are lucky that the Senate did not ratify that treaty and that President Bush pulled the U.S. out of the agreement.

The politicians lost to the scientists in FAR, but they didn’t give up. The second report (“SAR”) barely stepped over the threshold with the following conclusion:

“The balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.” (IPCC, 1996, p. 4)

Ronan Connolly and Michael Connolly (Connolly, 2019) explain that this statement was included in SAR because Benjamin Santer, a lead author of the SAR chapter on the attribution of climate change, presented some unpublished and non-peer-reviewed work that claimed he had identified a “fingerprint” of the human influence on global warming. His evidence consisted of measurements that showed lower atmospheric (tropospheric) warming and upper atmospheric (stratospheric) cooling from 1963-1988. This closely resembled a prediction made by the climate models used for SAR. He did not connect these measurements to human emissions of CO2, or to CO2 at all, he simply said that they showed something like what the models predicted. From the paper, published the following year:

“Our results suggest that the similarities between observed and model-predicted changes in the zonal-mean vertical patterns of temperature change over 1963-87 are unlikely to have resulted from natural internally generated variability of the climate system.” (Santer B. , et al., 1996a)

Pretty weak evidence, and it was evidence that had not been peer-reviewed or even submitted for publication in 1995, when the decision to include it in SAR was made. Benjamin Santer and Tom Wigley wanted the conclusion to read “appreciable human influence,” but Bert Bolin proposed “discernible” instead of “appreciable.” Bolin’s suggestion was adopted without objection (Darwall, 2013).

Santer’s paper was eventually published in Nature, on July 4, 1996, it was first received by Nature April 9, 1996. SAR, Climate Change 1995, The Science of Climate Change, Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC, 1996) was in final form and sent to the Cambridge University publishers in December 1995.

The fifth and final meeting of the IPCC SAR Working Group I was in Madrid, Spain from November 27 to 29, 1995, and was very contentious. They were debating, at the last minute, whether to change the already agreed underlying scientific reports in SAR so they matched the political Summary for Policymakers and “Technical Summary” as drafted by John Houghton, the senior editor and co-chairman of the volume with Gylvan Filho. According to Bernie Lewin, in his book Searching for the Catastrophe Signal (Lewin, 2017) the argument was largely between Dr. Mohammad Al-Sabban of Saudi Arabia and Dr. Benjamin Santer of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the United States.

The key portion of the report that Santer wanted to change was Chapter 8. Santer was one of the lead authors of the chapter and had written the first draft of the chapter in April, but now wanted to change it. The original April draft of the chapter is available, thanks to Bernie Lewin, and it concludes in part:

“…no study to date has both detected a significant climate change and positively attributed all or part of that change to anthropogenic causes.” (Lewin, 2017, p. 277)

Santer’s original draft of Chapter 8 relied heavily on another unpublished paper that he and Tim Barnett wrote with Phil Jones, Raymond Bradley, and Keith Briffa. The paper is entitled “Estimates of low frequency natural variability in near-surface air temperature.” It was later published in The Holocene (Barnett, Santer, Jones, Bradley, & Briffa, 1996). The paper forcefully makes the argument that long-term (i.e. low frequency) natural climate variability is not known accurately enough to detect the human climate change contribution with any confidence. The Holocene received this article July 17, 1995 and it was not approved and published until January 1996. In the conclusions of the paper the authors write:

The key message of this paper is that, if the palaeo [paleontological] data are reasonably correct and representative of large regions of the planet, then the current model estimates of natural variability cannot be used in rigorous tests aimed at detecting anthropogenic signals in the real world. (Barnett, Santer, Jones, Bradley, & Briffa, 1996), italics in the original.

Thus, they do not think that model estimates can detect human influence on climate. This conclusion was published a month after Santer, Wigley, and Houghton changed SAR to say that comparing a model to observations did just that. The conclusion of the final draft of Chapter 8, agreed to by all 36 authors, contained the following:

“we have no yardstick against which to measure the manmade effect. If long-range natural variability cannot be established, then we are back with the critique of Callendar in 1938, and we are no better off than Wigley in 1990.” (Lewin, 2017, p. 277)

They compare where they are, in July of 1995, to Guy Callendar’s classic 1938 paper (Callendar, 1938) and Tom Wigley’s chapter on Detecting the Greenhouse Effect in FAR (IPCC, 1990, p. 244). In FAR, on page 244, Wigley and the other authors of Chapter 8 write, “Natural variability of the climate system could be as large as the changes observed to date, but there are insufficient data to be able to estimate its magnitude or its sign.” Thus, they didn’t know how large the natural forces are, or whether they are working to warm the planet or cool it.

When the authors agreed to the wording of SAR’s Chapter 8 (page 409) in July, on the same subject, they still did not think they could detect a human influence on climate. John Houghton, the lead editor of the entire IPCC WG1 second assessment didn’t care what the authors concluded. He insisted that the young Benjamin Santer change the chapter and bring it into agreement with his summary.

So, the agreed statement saying “we have no yardstick” quoted above, was removed and the statement below added, without consulting the other 35 authors of Chapter 8.

“The body of statistical evidence in Chapter 8, when examined in the context of our physical understanding of the climate system, now points towards a discernable human influence on global climate.” (IPCC, 1996, p. 439)

The agreement of all chapter authors had been reached in July of 1995 to say the opposite. Another paper of Santer’s, published in Climate Dynamics in 1995, “Towards the detection and attribution of an anthropogenic effect on climate” (Santer B. , et al., 1995), states, “This analysis supports but does not prove the hypothesis that we have detected an anthropogenic climate change signal.”

Santer’s 1996 “fingerprint” paper, published after SAR came out, admits that they did not quantify the relative magnitude of natural and human influences on climate. They simply showed a statistically significant similarity between some observations and their model’s predictions. As weak, and as new, as this unpublished study was, it was accepted as proof of a “discernable human influence” on climate change.

They made the last-minute change to SAR a month before Barnett and Santer’s paper came out explicitly saying, “current model estimates of natural variability cannot be used in rigorous tests aimed at detecting anthropogenic signals.” (Barnett, Santer, Jones, Bradley, & Briffa, 1996). The contradictions were glaring.

The political pressure from John Houghton, a Welsh atmospheric physicist, who was the lead editor of the first three IPCC reports, was unrelenting. Santer and the other attendees at the November 1995 final meeting in Madrid on SAR felt they had to do something. The group settled on the yet-unpublished “fingerprint” work that Santer had nearly finished (Santer B. , et al., 1996a).

On November 27, 1995 Santer presented his work to the assembled group and John Houghton. Houghton formed an ad hoc committee to review Santer’s work. The hand-picked committee voted to change Chapter 8 and bring it into line with the drafted Summary for Policymakers.

On the last day of the meeting, November 29th, the group debated the changes to the already agreed Chapter. The Saudis and the Kuwaitis were insistent that the unpublished findings should be presented as preliminary. This had the advantage of being true, the statements hinged on an unpublished study.

The debate went on for many hours. The Saudis, led by Dr. Mohammad Al-Sabban, wanted the summary to revert to the agreed text and conclusions of the original agreed chapter. Most of the others disagreed. The majority prevailed and at 10:30PM, November 29th, the group settled on the final wording, “The balance of evidence suggests a discernable human influence on climate.”

Word that unpublished and non-peer-reviewed work had caused the IPCC editors to change the agreed text of Chapter 8 got out. The changes turned critical statements on the detection of human influence on climate change 180 degrees. The statements went from (paraphrasing) “impossible to tell if it exists” to a “discernable influence.”

Frederick Seitz, who was the 17th president of the United States National Academy of Sciences from 1962-1969, was horrified by this action and wrote about it in the Wall Street Journal (Seitz, 1996), under the headline “A Major Deception On Global Warming.” The late Seitz was a hugely influential scientist, but the IPCC lost his support and the support of hundreds of other influential scientists by caving to the politicians.

Bernie Lewin identified this 1995 meeting in Madrid as a key turning point in the climate change debate. Judith Curry agrees with his conclusion (Curry J. , 2018). The removal of agreed statements from a technical chapter to agree with unsubstantiated political opinions greatly hurt John Houghton’s cause and reputation.

Seitz’s allegations were contested (Avery, Try, Anthes, & Hallgren, 1996). An open letter to Benjamin Santer was published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS) supporting him. The letter explicitly mentions the article by Frederick Seitz in the Wall Street Journal. It states that the proper place to debate scientific issues is in peer-reviewed journals and not in the media where Seitz published his critical essay. This seems quite hypocritical to this author, as peer-reviewed material was removed by the managing committee of the IPCC and replaced with the unpublished opinions of John Houghton and Benjamin Santer. In any case, the facts are the facts, the original approved draft of Chapter 8 exists, and it was changed by Houghton’s supervising committee after review and without consulting most of the authors of the chapter. The facts are clear.

Benjamin Santer admitted changing the draft chapter eight at the behest of the governments but tried to insist that the changes didn’t matter (Santer B. , 1996c). Rupert Darwall argues that if they didn’t matter why did the governments want them changed? (Darwall, 2013, Kindle 6319). John Houghton reports in Nature (Houghton, 1996) that one of the governments that pressured him to change Chapter 8 was the United States. He wrote that the U.S. found several inconsistencies and “that the chapter authors be prevailed upon to modify their text in an appropriate manner following the discussion in Madrid.”

John Houghton wrote that “the IPCC is a scientific body charged with producing scientific assessments.” (Houghton, 1996). It clearly is not. The governments funding the IPCC have the right to force these changes, but they can’t change what the scientists write and claim the document is scientific. It is either a political document or a scientific document, it cannot be both.

Unfortunately, when Santer’s fingerprint paper (Santer B. , et al., 1996) was finally published it ran into a firestorm of criticism. In particular, Dr. Patrick Michaels and Dr. Paul Knappenberger (Michaels & Knappenberger, 1996) pointed out that the tropospheric “hot spot” that comprised Santer et al.’s “fingerprint” of human influence disappeared if the 1963-1987 range was expanded to the full range of available data, 1958-1995. In other words, it appeared Santer, et al. had cherry-picked their “fingerprint.”

There were other problems with Santer et al.’s interpretation. The warming and cooling trends that they identified may have been natural, as explained by Dr. Gerd R. Weber (Daly, 1997). The beginning of Santer, et al.’s selected period was characterized by volcanism and the end of the period by strong El Niños. The SAR Chapter 8 scandal left a lasting stain on the reputations of the IPCC, Benjamin Santer, and John Houghton. The whole episode is an example of politics corrupting science.

This is a condensed excerpt from my new book, Politics and Climate Change: A History.

To download the bibliography, click here.

Andy May, now retired, was a petrophysicist for 42 years. He has worked on oil, gas and CO2 fields in the USA, Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia, Thailand, China, UK North Sea, Canada, Mexico, Venezuela and Russia. He specializes in fractured reservoirs, wireline and core image interpretation and capillary pressure analysis, besides conventional log analysis. He is proficient in Terrastation, Geolog and Powerlog software. His full resume can be found on linkedin or here: AndyMay